Prolonged QTc, Long QT Syndrome and CCDS: Q&A with Dr. Mark Levin

Dr. Mark Levin is a board certified pediatric cardiologist at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Heart, Lung & Blood Institute (NHLBI), and has gained experience working with Creatine Transporter Deficiency (CTD) patients through his work on the Vigilan Observational Study. Dr. Levin presented at the 2021 CCDS Virtual Conference on “Cardiac Abnormalities in Patients and Animal Models of Creatine Transporter Deficiency” and a video of his presentation is available on the ACD YouTube channel.

Dr. Levin completed medical school at Boston University, a pediatrics residency at Columbia Presbyterian in NYC, and a pediatric cardiology fellowship at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. He subsequently completed advanced training in non-invasive clinical cardiac electrophysiology also at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia as well as post-doctoral research fellowships in molecular cardiology at the University of Pennsylvania and cellular ion channel physiology at Washington University.

ACD recently followed up with Dr. Levin with an interview to answer some questions to help improve the CCDS community’s knowledge and awareness of potential cardiac issues in CCDS patients.

What is an EKG used for? What do the readouts represent?

An electrocardiogram (also known as an EKG or ECG) is a 6 second recording of the heart’s electrical system used to measure and analyze how well the heart’s electrical system is working to coordinate the heart’s blood pumping functions.

As background, the heart is a pump with two big chambers (ventricles) and two small chambers (atrium). The heart’s electrical system coordinates the beating of these chambers so blood can reach parts in your body efficiently. The EKG is a snapshot that shows three distinct electrical events (or signals) that occur in the heart as part of this process:

- The first signal is called the “P-Wave”. It looks like a small squiggle on the EKG readout and represents the excitation of the small chambers (atrium). It acts as the “get ready” signal. This is followed by a short flat line, which is a time delay that lets the big chambers (ventricles) catch all the blood that should go out to the body.

- The second signal is the biggest wave on the EKG readout and is called the “QRS” complex. This is also an excitation event. This signals the big chambers (ventricles) to squeeze and push blood to the body. Think of this as the “on” signal.

The third signal is the “T-Wave” and is also referred to as repolarization of the heart. This is the reset signal, telling the salts in the heart (on/off signals) to get back to where they started so they can signal “on” again. This signal tells the heart to relax or “resets”.

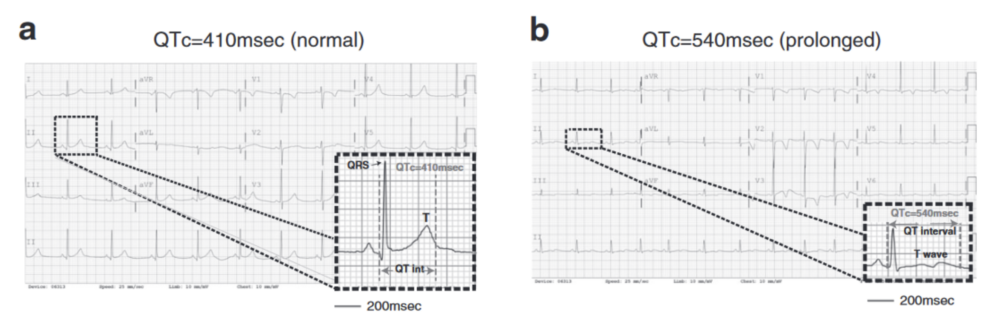

Figure 1: ECG of a normal QTc (left) and prolonged QTc (right). (Levin et al., 2021)

What is “Prolonged QTc”?

The time between the QRS signal (lights on) and the T-Wave signal (reset signal) is measured. Really, most of the problems directly relate to the reset signal. So the best way to determine if there is a reset signal problem is to measure the time it takes to turn on and reset. This time is the QTc. If the time is longer than typical, we say the QTc is prolonged. This can be caused by gene abnormalities in the proteins that handle salts in the heart; specifically, the ion channel proteins. Most often, the genes involved are related to handling potassium, a salt very important in handling the reset signal. When the QTc is 470 milliseconds (msec) or greater, then doctors get concerned that the person might have an increased risk of heart abnormalities. Your doctor may describe this as prolonged QTc. Prolonged QTc implies there is uncertainty about whether that person has a risk of a bad event. These events are very infrequent, even in patients who we know have these abnormalities but we still try to be very cautious and minimize the likelihood something bad might happen.

What is Long QT Syndrome? How is it different from Prolonged QTc?

Typically, Long QT is caused by one of four different genes (but there are at least 13 known causes). There are issues with the proteins that usually regulate the salts in the heart (ion channels; these act as gateways to let salt in and out of heart cells). As an analogy, these channels have ‘gates’ or ‘doors’ and sometimes the door cannot shut all the way, so the salts leak and spread to locations where they should not. This is what can cause the T-Wave to show longer (meaning it takes more time to reset) than what is typical. A person with “Long QT Syndrome” may have a prolonged QTc interval on their EKG, but they also have a number of other disease- or family-features that are present. These features suggest either they or a first-degree relative have had an event characterized by sudden death or what we call “abortive” sudden death; this occurs when that person can be resuscitated and “saved” from the bad event. About 90% of the time people have a genetic mutation in one of two genes that handle potassium in the heart (about 8% of the time it involves a gene that handles sodium in the heart). Importantly, in general the length of the QTc correlates strongly with the amount of risk in that person. Specifically, if that number is near or over 500 msec, studies show that person may be considered “high risk.” In general, if that number is over 470 msec, it’s good for that person to see a cardiologist familiar with treating patients with this problem. The cardiologist can help determine whether that person may be at increased risk and what, if anything, can be done to assess or minimize that risk.

Are Prolonged QTc or Long QT Syndrome issues for CCDS?

We have noticed a lot of kids with CTD have prolonged QTc and a high proportion of them have QTc’s near or over 500 msec. It is unclear what this means, and we are working on ways to better understand what causes this and what the true risk this poses. While there is a lot of uncertainty as to what this might mean, the safest route is to try and reduce risk if we can. We recommend that patients with a new diagnosis of CTD have a cardiac evaluation, including having an EKG, an echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart), and meet with a cardiologist to discuss these results and what this information could mean regarding risk in children and adults with CTD. Currently, it is unknown if this is an issue with AGAT and GAMT patients.

How would I know if my child has this? What would I expect to see?

If your child is having prolonged QTc you may not notice anything. That is why we recommend that you have your child seen by a cardiologist for an evaluation. Additionally, there are a few “red-flags” that should prompt additional evaluation and potential concern:

- Fainting Spells

- Almost-fainting spells

- Fast heart rate for no reason (also known as palpitations). This might be noticed because a child is breathing heavily and sweating when inappropriate, such as while watching television or playing a tablet.

- Difficulty exerting oneself. For example, a parent might say “Felix used to be able to walk around the block without a problem, but for the past month he can’t.” This would be different than if someone has a virus or is recovering from a virus.

- Sometimes you cannot completely articulate the problem, but you have a “gut feeling” that something is not right. I tell parents if they have a “gut feeling” something is not right, give me a call and we can talk.

Importantly, a bunch of simple, non-concerning things can also cause some of these symptoms. The most common one is dehydration, so I always tell kids and families to make sure they drink a lot of water. Most people drink much less water than they should (including me). Doing so may help you avoid the worry of having symptoms that overlap these cardiac concerns. In general, it is important to have a cardiologist evaluate the symptoms to better determine their cause and establish what needs to be done.

Are there things I can do to help minimize my child’s risk if my child has prolonged QTc?

Yes, but allow me to give a bit of background first. In addition to what is called “congenital” Long QT Syndrome which is when a child has a known or suspected genetic abnormality in an ion channel gene, there is what is called “acquired” Long QT Syndrome. This is when a person takes a medicine that can make their QTc prolonged. I think of kids with CTD as being in this category. Your cardiologist may want to do genetic testing to make sure your child doesn’t have a gene defect in one of the genes that cause “congenital” Long QT Syndrome, but that is going to be pretty uncommon to have two rare abnormalities at the same time. More likely CTD is causing some change in the heart that indirectly affects ion channels there. There are lists of medicines that people with congenital or acquired Long QT Syndrome are suggested to avoid. The one I suggest is at crediblemeds.org. In general, if your doctor wants to start a medicine that is on this list, it is probably best if they can avoid doing so. Sometimes, it can’t be avoided. One example is a very important asthma medicine called albuterol. It can truly be a lifesaver and there really is not any medicine as effective as this one for the circumstances where we use it. In the case of a child who has asthma, you can’t avoid using that medication sometimes, but there are other medications you can use that may make the need for that medicine less likely. The other thing we like to tell parents is that if your child with CTD has a fever, it is very important to treat that fever with tylenol or an equivalent. Untreated fever can worsen the QTc abnormality but treating the fever can prevent that from happening.

If prolonged QTc might not show symptoms, how do I find out if this is affecting my child?

I recommend that patients receive an EKG and an echocardiogram around the time that they are diagnosed. If your child has metabolic disturbance around the time this diagnosis is made, it may be helpful to wait or repeat the EKG and echocardiogram after those metabolic abnormalities are gone because those problems will cause abnormalities in both tests. Again, you should discuss these results with your cardiologist and you can always offer that I would be happy to discuss the test results with them as well as. In general, it would be reasonable to have a yearly “screening” EKG. Echocardiograms could happen less frequently: at least once at diagnosis, once before/early adolescence, and once late adolescence. If your child shows symptoms like those listed above, that would be a reason to confer with a cardiologist who may decide to repeat these tests. Also, it may be helpful to repeat an EKG before and after some medications are started. As I mentioned, it is helpful to check the list of QT prolonging medications before starting a medication. Be aware that not every medicine that prolongs the QTc is on that list. There are some drugs that may prolong the QTc which have not been reported. Additionally, everyone responds to medication a little differently. There are some great important helpful drugs that affect the brain, preventing seizures or helping with anxiety or depression for example. Many of these medicines also work on ion channels (proteins handling salts in the brain), and drugs that can affect ion channels in the brain have unexpected effects on ion channels in the heart. For this reason, I recommend having an EKG approximately a month after starting the medication to make sure it’s not prolonging the QTc. Sometimes that medication is necessary, but it’s better to know where you stand with respect to these risks and sometimes there are some things you can do to mitigate these risks.

Does a Prolonged QTC hurt my child?

The Prolonged QTC itself doesn’t hurt your child per se. It’s a sign that a doctor can help you interpret that may or may not correlate with a risk. I think of a prolonged QTc as having extra lottery tickets for a lottery you don’t want to hit. In itself, you don’t feel it, but it can tell you the likelihood of a future event. In this case, the event we are worried about is a heart electrical abnormality, an arrhythmia, or even sudden death.

My child has Prolonged QTC. Now what do I do? How do I reduce the risks associated with this?

Your doctor may monitor your child’s sodium, potassium, and magnesium levels. They may also prescribe a beta blocker and advise you to avoid certain medications. Again, the website crediblemeds.org lists most of the drugs that are not safe for prolonged QTC and Long QT. There will be occasions when your doctor may recommend a drug on that list because they believe the benefits outweigh the risks. This would need to be something you discuss with your doctor.

In cases where your child may have had a dangerous arrhythmia or a worrisome “syncopal” event (passing out from arrhythmia), your doctor may recommend implantation of automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (AICD). This is similar to a pacemaker (it can also function like a pacemaker) and it can detect an abnormal heartbeat and send therapies like an electric shock to reset the heartbeat.

If there is a relationship with salts, is there anything I can do to help with my child’s diet? Or do I need to avoid salts?

The best thing you can do is make sure your child does not become dehydrated. There are many different opinions on the amount of water to drink per day, but the best measure of if you are drinking enough is to observe the color of your child’s urine. If it is a light or clear color, they are probably well hydrated. If it is dark yellow, you likely need to increase their fluid intake.

My child was given an E-Patch (or Z-Patch) to monitor their heart. Would that catch a Prolonged QTC or Long QT?

Not really, but those can help to look for the effects of the prolonged QTc. Again, with a prolonged QTc, we worry about arrhythmias, heart electrical problems. Things like Ziopatch or E-patch can record heart electrical activity for days or weeks. This allows us to see what’s going on in the heart when someone has symptoms, for example. These are not a replacement for an EKG, though. They serve other purposes, but if you have CTD, an EKG is still recommended.

What is the impact of a creatine deficiency on the heart?

That’s a great question and one we are actively working on right now. The short answer is we don’t know right now, but we are trying to figure out what the impact is.

My child appears to faint and has appeared to have seizures, but we were told those were breath-holding spells. Could this be related to a prolonged QTC?

That’s a great question and requires a complex answer. One of the reasons we wanted to try and get this information out to families and doctors taking care of CTD patients is that we know sometimes things that look like seizures can actually be caused by heart problems such as arrhythmias. Some heart problems can cause seizures because the heart problem prevents good flow of blood to the brain which is what can cause seizures. For this reason, we are recommending that your child have a cardiac evaluation to make sure that there is not an underlying heart problem that should be addressed. Breath-holding spells, seizures, and arrhythmias from prolonged QTC can all cause similar symptoms. It can be very tricky to tease out what might be responsible for these events. I would recommend discussing this with your physician and informing them of the prevalence of prolonged QTC in patients with CTD.

Thanks for the opportunity to speak with all of you. I’ve really enjoyed it. Please remember that if your physician has questions or concerns, I would be happy to discuss specifics further. You can best reach me at: mark.levin@nih.gov. Thanks!

Disclaimer: The opinions shared in this post are meant to increase awareness and discussions around the care of patients with a CCDS. This blog is not intended as a substitute for medical care by a physician. Do not make any changes to your care, or your child’s care, without your physician’s direct involvement, supervision, and approval.

References: