“The One in the Middle” – Beth

With the GAMT diagnosis of two of our children, our unaffected middle child immediately became the odd man out. Even my husband and I, given our genetic contribution to the disorder, were involved somehow. But Mae, our middle child, has no ties to the disorder as of now.

This seems like a good thing. And it is, but it puts her in a unique situation. Mae has observed from the sidelines. She has stayed home with grandparents while we are at the hospital for long stays. She has visited her sister in the hospital after surgery. She has tagged along for long days at the hospital for clinic visits. She has heard me arguing with insurance over the phone. She has forgone ice cream store visits because her siblings couldn’t have that much protein. She has coaxed her brother out of the car when he’s refusing to move during a tantrum. She has given up her spot at the couch when we’re watching TV so I can administer medication to her sister. And lately, she’s started to understand how cruel the world can be. Despite (or because of) this recent development, she’s going to grow up to be tolerant, compassionate and patient. She’s an

The most obvious effect is a little jealousy. It’s understandable. The other two get special appointments and meetings at the hospital and at school. They get showered with attention during these meetings.

Even when the GAMTers need medical procedures, Mae gets a little jealous. Along with the medical procedures come rewards of toys and treats and praise. We anticipate her jealousy and try to give the one in the middle what she really craves—our attention and time.

When we first began treatment, the GAMTers adhered to a very low-protein diet. This meant cutting out meat for sure, along with other high-protein foods. Mae saw what a struggle this was for them and, while she couldn’t safely eat low-protein like the other kids, she decided to also remove meat from her diet in a show of solidarity. She was only eight when she chose to do this. She did eventually add meat back into her diet. But for her to choose to walk in their shoes for a short time was a sign of just how remarkable this girl is.

I think the most beautiful development is how she sees the world. She’s been trained to look for those who might need a little more help. To look for those who might need a friend. To look for those whose lives are different than ours. To look for the gratitude in any situation.

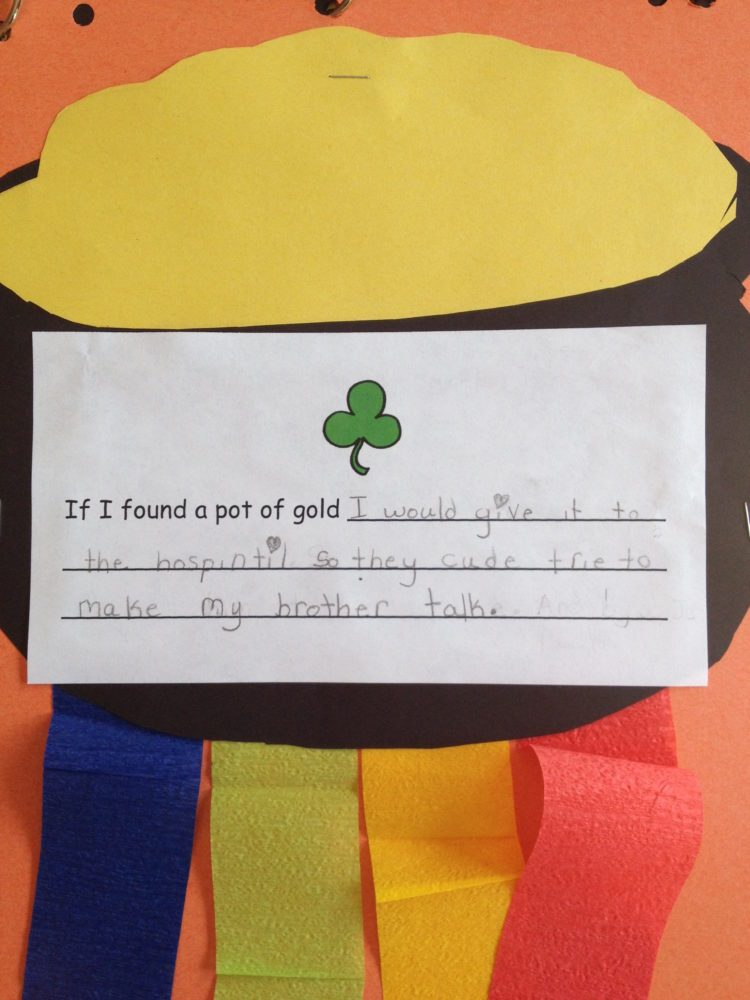

She’s a reflective girl and it’s one of the many things I love about her. I can see her sitting quietly, turning over thoughts in her head. One thought that stuck with me was about her non-verbal brother with special needs. With innocent sincerity, she wondered aloud, “do you think Benny talks in his dreams?” The weight of this question still sits on my heart. I answered as best I could, “I don’t know, Mae.” I had never thought of it. But what a beautiful and poignant question. I love that she looks at people and takes time to think about their lives like that.

We’ve had to talk to her about the world and how others see our family. There came a time when we had to explain that people are staring at us because her brother is making funny noises or he’s flapping and jumping in excitement. And we are honest with her—most of the time, children are just genuinely curious about Benny and maybe we can intervene and help people understand. But there are other times when we can’t explain away adults’ poor behavior. We chose to tell her about the dreaded “R-word.” The one used to make fun of people with special needs. She’s going to hear it and we wanted to be the ones to explain it to her, to make sure she knew what it meant, knew the implications, and knew how much it hurt our family. She cried when she understood that people could use that word to make fun of someone like her brother. After the initial sadness over this realization, her view of the world is simpler. Some people get it and some people don’t. She spends the majority of her time and energy on the ones that get it. And that’s a pretty practical way to face the world.

I spent several years worrying about how being caught in the middle of this diagnosis would affect her. It was one of my first thoughts after getting our diagnosis. I now realize that every family has some thing.

Something that affects their family and influences their growth, whether good or bad. I shouldn’t feel too much guilt over this. I can’t feel guilt over this. I think our family dynamic and her role in this diagnosis has led her to a place of understanding, compassion, empathy, and kindness. It’s a beautiful thing to watch and I couldn’t be more proud of the one in the middle.