Creatine Transporter Deficiency – Judith Miller, PhD

By Judith Miller, PhD, and Rebecca Thomas, MA – The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Creatine Transporter Deficiency (CTD) – work presented at the Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics conference in Savannah, GA.

As CTD families, you have probably spoken with others about your own experience – what the first signs of CTD might have been, how your child got the diagnosis, what your worries for the future are. We at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia just finished a pilot study of CTD focused on this and other topics, and we recently presented our first set of data to The Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatricians (SDBP) in Savannah, GA on September 16-19, 2016. Thanks go to all the families who participated, and to our colleagues at both Lumos Pharma, Inc. and the National Institute of Mental Health for their contributions.

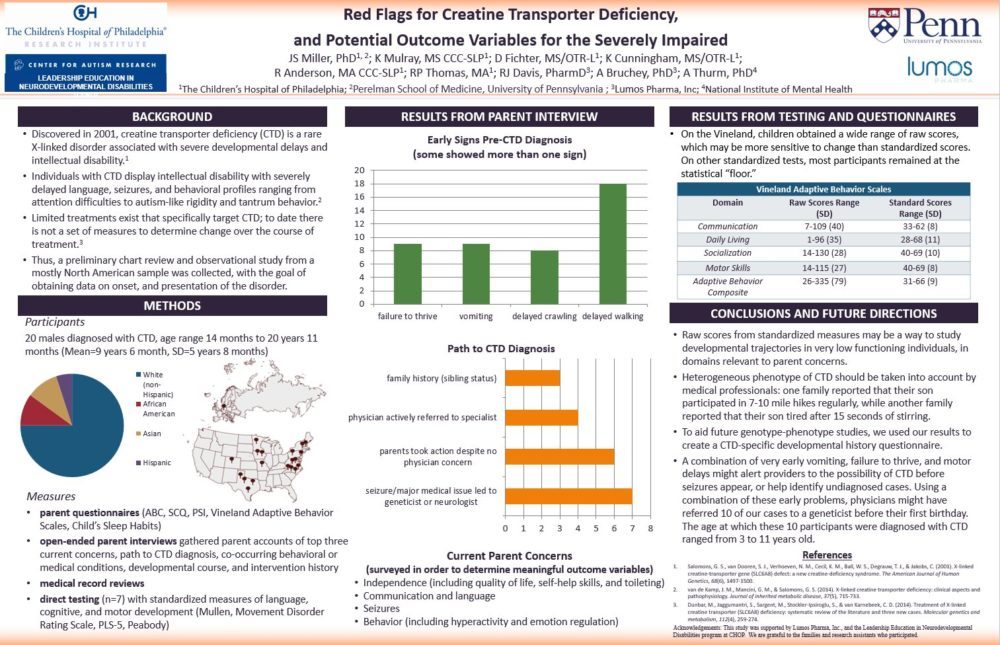

This first analysis focused on one aspect of the study — the information we got from parents. We interviewed the parents of 20 children and adults with CTD about their path to the diagnosis, what their child’s early history was like, and what the parents’ current concerns are. We hoped to uncover some early signs of CTD that might improve detection and earlier diagnosis. We also hoped to identify what parents’ priorities are now. What kinds of improvement would be meaningful enough to know that a treatment is working?

Families were incredibly generous with their time – we interviewed each for about an hour by phone, and then asked them to complete extra questionnaires, share medical records, and share home videos. Families from across the country and Europe participated, with children ranging in age from 14 months to 21 years old. As a study team, we then put all the information together to identify common experiences and perspectives across families.

Our parent interview was “unstructured,” meaning we had a short list of general questions, but we really let the families tell the story their own way. This definitely led to some findings that we think are going to be really helpful moving forward, in areas that we wouldn’t have thought of on our own. Parents described some pretty similar causes for concern in their child’s development. Most talked about delayed crawling and walking, early projectile vomiting, and significantly below-average weight, sometimes diagnosed as “failure to thrive.” We looked back at the medical records to try to figure out the specific ages of these first concerns.

We found that half of our participants could have been referred to a geneticist before their first birthday if the combination of early vomiting, failure to thrive and delayed crawling or walking had alerted the pediatrician. The kids in this group were actually diagnosed between ages 3 and 11 years. That’s a big gap in when the warning signs appeared and when the diagnosis was actually made! We hope to study this more, and learn the best way to alert pediatricians about this combination of signs.

It was fascinating to hear parents talk about the different ways they arrived at a CTD diagnosis. One thing that stood out in every interview was that the families we spoke to are extraordinary advocates for their children. Of the 20 children, four had support right away from their pediatrician, though it might have taken several specialty evaluations before an accurate diagnosis was made. Parents of six children had to seek specialists out themselves because their pediatricians were not concerned. Seven had medical issues or seizures that led to specialist evaluations. And three had an older sibling with CTD which led to testing in the younger sibling.

Of course, after the diagnosis is made, the question shifts from “what is going on?” to “what can we do?” We asked parents for their top three current concerns. There was a lot of overlap, suggesting that parents share similar worries about their children’s futures. Most parents were primarily concerned about independence, quality of life, communication, and seizures. Our goal is to map these concerns onto outcome measures in clinical trials. This will allow us to create treatments that directly relate to parents’ priorities.

So where do we go from here? First, we took the information from the parent interviews and created a CTD-specific developmental history interview. It covers all the areas parents mentioned in the phone interviews. We are going to make it publicly available so other researchers and physicians can use it, which we hope will lead to more comprehensive information asked in a consistent way across researchers and providers. Second, we have more data to analyze! We are currently analyzing the questionnaire data, to see which measures provide good data on the areas parents prioritized. In addition, 7 of the 20 children were able to come to our lab for direct testing. We pilot-tested a variety of developmental tests with them, to help pick the best tools for a future clinical trial, and will use that information to design a longitudinal study. And of course we’ll submit all our findings to a scientific journal so it can reach the broader audience of researchers, pediatricians, neurologists, and geneticists.

All the work we are doing will help us design the best clinical trials possible. If you’d like to get involved, let us know! We view families who participate as VIP donors – on the same playing field as donors who contribute millions for new buildings or new research programs. We can’t conduct research without you! So don’t hesitate to let us know how we can make it easier to participate.

This study was conducted by the Center for Autism Research at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and was funded by Lumos Pharma, Inc. Thanks to all the children and families for their participation. If you would like to receive information about future studies, please contact Rebecca Thomas at thomasrp@email.chop.edu.